The questions I’m most interested in continue to move me farther away from the publishing hustle, and closer to what the decay of such an industry might mean. In recent days, this has taken shape quite literally, in leaving a book outside in my yard. I want to see how and where it begins to disintegrate, and I want to see how I feel as it does so.

At first, I felt resistance. I love my books, and I try to take good care of them. They contain messages from writers and friends and mentors. When money is tight, I manage to cull and sell some. A few I’ve held onto for most of my life, the only objects to accompany me through many moves thousands of miles away from my hometown. Others connect me to personal histories of jobs held and classes taught, formative teachers, and histories of movements and ideas that I summon just by looking at them on their shelves; in doing so, my books become a totem of certain aspects of my identity. Thinking about losing them is painful. Palestinian poet Mosab Abu Toha writing in The New Yorker on November 7, 2023, just days before he was taken prisoner by the IDF, captures this feeling devastatingly realized after the destruction by Israel of not just his home but all of his books, too, which he spent years painstakingly acquiring. Here, in Portland, I am surrounded by bookstores large and small, used and new; I can order most books delivered to my home, or (more often) find them through the library system; my favorite local bookstore where they know me by name is a 15 minute walk from my house. The acquiring of books can easily be taken for granted.

All of which is to say, leaving a book outside on purpose is not something I do cavalierly. But I’m also not the only one. The Merwin Conservancy, which stewards the home and extraordinarily diverse palm garden W. S. Merwin cultivated in Haiku, Hawai'i, on the island of Maui, has taken care to leave untouched the books the poet kept outside in his garden. They’re allowed to decay and return to the earth in what Merwin called his “bio-piles.” Yard work is not my forte. About one third of our lawn (we still rent) is taken over by invasive Himalayan blackberry vines that spill over from the neighbors. So while my garden has been neglected this last year, I am exceedingly good at leaving things in one place and watching how they change, without my interference. And once the idea took root in my head to “read” a book by how it breaks down, I couldn’t shake it.

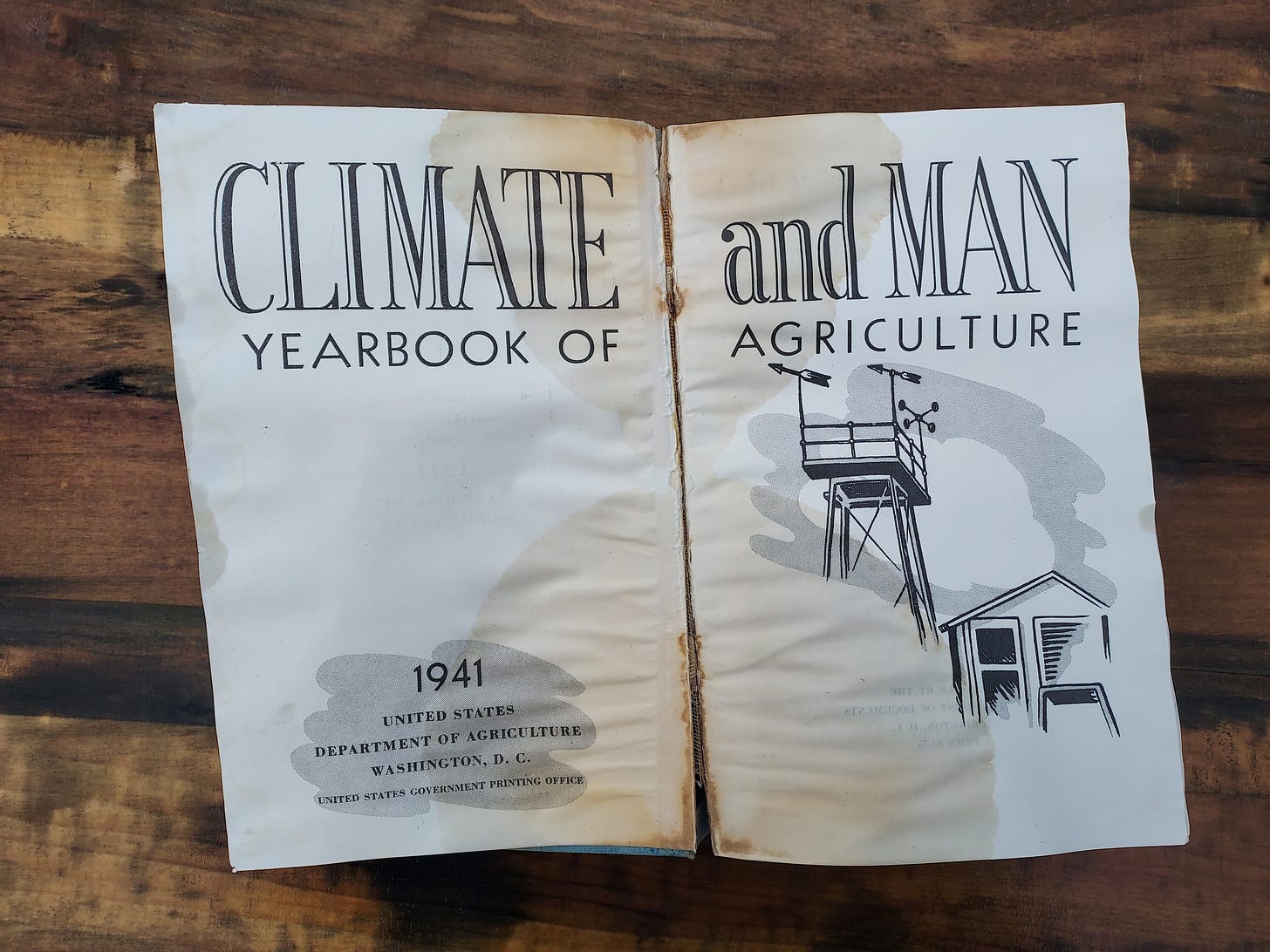

The choice of a book was easy. Some time ago I found “Climate and Man” in a used bookstore. Published by the USDA in 1941 at a time when the consolidation of land in the hands of white landlords was rapidly being bureaucratized, the bulk of its pages contain isothermal maps laying down bands of differently shaded temperature across the nation, as well as charts relaying monthly temperature averages and extremes for every single county. There is no talk of climate change in the present “age of man,” as it hadn’t entered the lexicon yet, and what text there is mostly concerned with pest management, freezes and floods, and how white European Americans can improve their crop yield and mechanize faster in their respective climates. (If interested, you can read the full text online at the Internet Archive, along with every other USDA yearbook.)

I could pore over a book like this for hours, and I have. I find historical perspectives on what climate is and means endlessly fascinating. But what would the rain think?

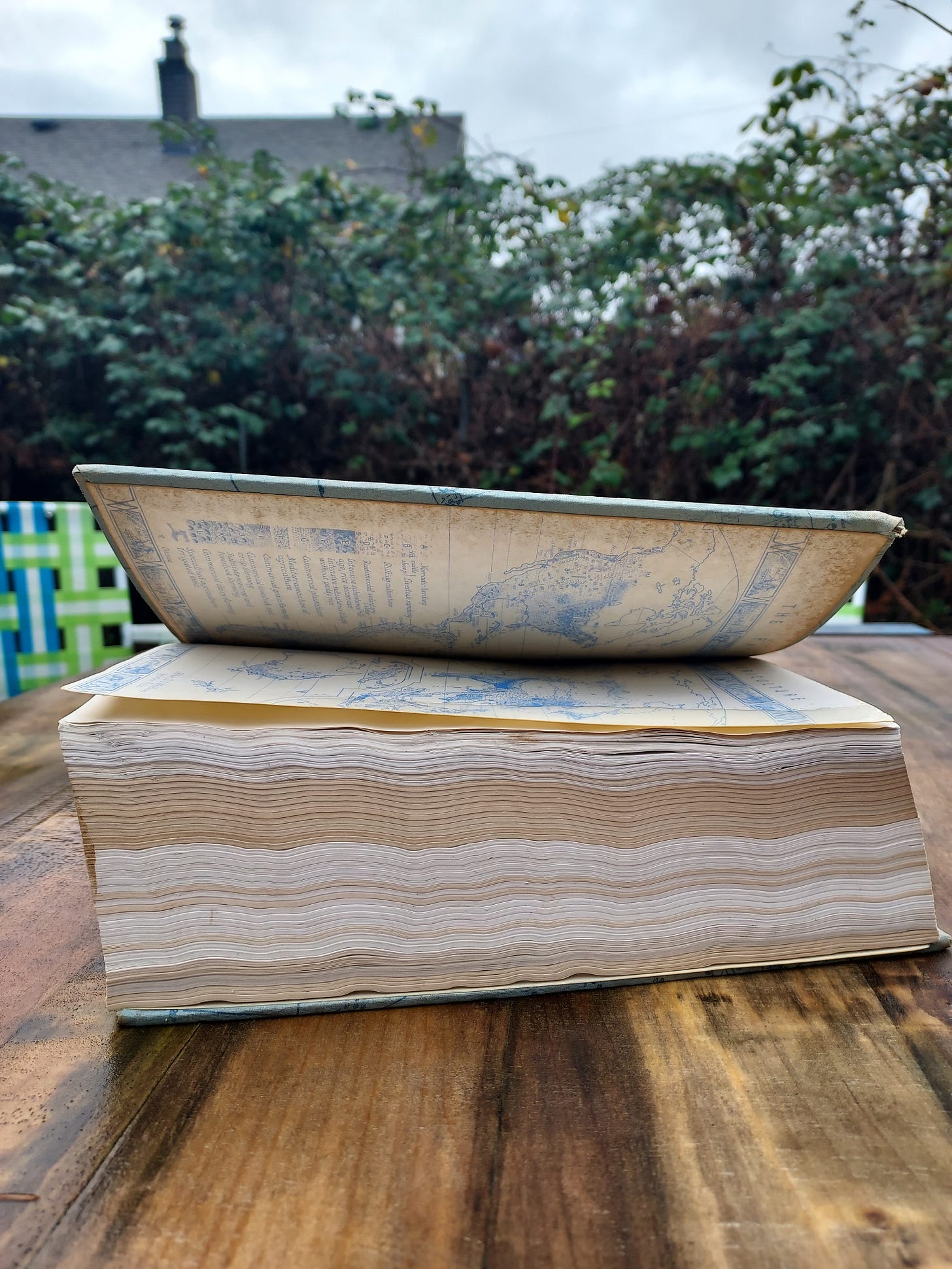

Now every morning I wake up and look to see what’s changed in Climate and Man—a ski slope cover, geological layers of rain-swollen pages, endpapers of the map of the world slowly losing their adhesive and wrinkling so that they become an unreadable, soggy terrain. As the weather reads about itself, what does it think about this biography? How would it tell things differently

back when I could flood with no one to drown

when there was no one around to shape me in their own image, only crows to play in my snow

no men and no women to mistake my weatherthem

when i could gray for days and not feel guilt, bake the earth and not hear hunger, storm without expectations, season however and wherever i wanted, unforeseen

no one to concentrate the sap i set flowing, to harvest the berries and nuts i ripened, to celebrate the first trickle of water i thawed

This is a fun exercise, but I have no desire for an unpeopled, unhistoried land. I don’t think the weather does either. One of the silences I’ve been exploring lately has been what human stories about weather might mean to the weather itself—how it would remember us, given the chance. It feels important to emphasize that this is an exercise in perspective. I’m not interested in the nonhuman as a negation of the human, a self-indulgent thought experiment imagining the future earth depopulated post-climate disaster. I tend to think this is a dangerous offshoot of contemporary climate writing that makes space for continued harm and environmental degradation in the present (i.e. “anyone worth saving will have left on a rocket ship long ago.”) Thinking outside of ourselves and our perspective, thinking about people from the perspective of a weather system, doesn’t have to mean imagining our own destruction.

I remember visiting my Seventh Wave friends in Seattle on a weekend full of bluster and heavy rain, when Joyce, who grew up in L.A., said she’s always liked the rain because people seemed friendlier in a downpour. Holding doors, providing shelter, peeking around hooded raincoats with childlike smiles. Alain de Botton asserts the opposite about bad weather. In his book The News: A User’s Manual, he writes that it was easier in ancient Athens for citizens without large institutions of journalism to take the pulse of their society “thanks to good weather, a small and cohesive city centre, and a culture of democratic conviviality.” He continues: “But we aren’t so blessed. Our cities too big, our weather patterns too unpredictable, our democratic systems too indirect and our homes too widely scattered.”

It’s a strange argument, the notion that bad or unpredictable weather discourages enough people from congregating outside and therefore necessitates news organizations and their practices of disseminating information. But when it begins to hail, who doesn’t step outside for a better look? In Portland, Maine my favorite bar halved the price of a pint during nor’easters, ensuring they were packed. When I went snowshoeing in a rare snowfall in my neighborhood in the Portland that’s now my home, neighbors stood and grinned in their windows; they lifted up the baby for a better look and waved excitedly. Even when confined to our homes by smog or heat or blizzards, we’ve got many more windows on the world now than we once did, more ways to connect.

Weather is the least lonely thing.

Upcoming

If the silences have been calling you, I’ve got two classes starting soon that you may find interesting: Chimeric Writing starts January 21, where we’ll be reading Daniella Cascella, JJJJJerome Ellis, Colleen Burner, and Adania Shibli, in our exploration of that which cannot be approached directly. Then, beginning February 8 is a new session of Notions: A Sewing & Writing Class, which is just what it sounds like ~

As a final celebration of the work of my first Short Story Multiverse cohort, we’ll be holding a panel & reading on Wednesday, January 17 at 4pm PST on Zoom. Registration is free and open to the public. The work of these four writers, artists, and amazing people spans from short stories to hybrid forms, hypertext to movement and web comics. It’s not an exaggeration to say they’ve changed my own conception of what a multiverse can mean, and I hope you’ll join us to hear their work and their questions for one another (and you?!)

Interesting to actually contemplate books deteriorating in weather. I sometimes bought books in used bookstores because they were weathered.