I don’t believe in the power of story.

I'd just spent my first year in grad school for creative writing watching one of the brightest stars, Zoe Rana Mungin, the only black woman in our program at the time, be pilloried by students, administration, and professors, all while remaining a rock for those of us entering the MFA trying in vain to defog the glass of literature. I was searching for answers, about whether trying to write at all was the best way forward in this milieu, and I found The Racial Imaginary, edited by Claudia Rankine, Beth Loffreda, and Max King Cap. In their introduction, the editors address those who ask, when faced with criticism of their portrayal of characters of a different race, ethnicity, or identity than them: "do I not have the right to write about others who are different from me?" To which they respond:

We’d like to change the terms of the conversation. [. . .] to ask why and what for, not just if and how? What is the charisma of what I feel estranged from, and why might I wish to enter and inhabit it? To speak not in terms of prohibition and rights, but desire. To ask what we think we know, and how we might undermine our own sense of authority.”

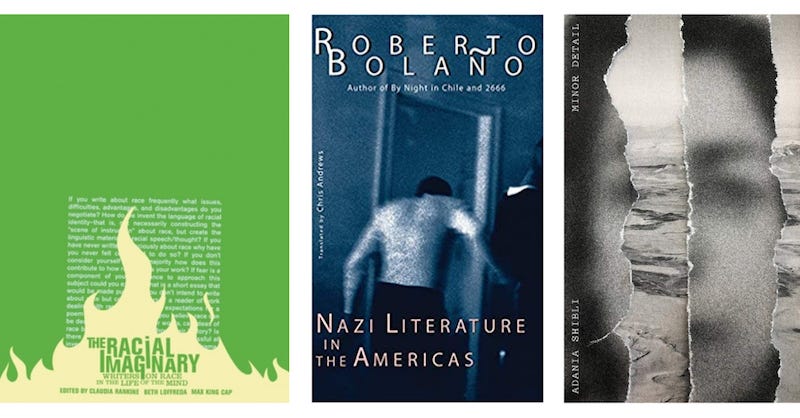

To me, this was extremely interesting. Many people and literatures have answered this question differently, and some have totally elided the question altogether; here in the United States, we are obsessed with it. And yet, I couldn’t then think of a book that was trying to answer this question. It's not a question you can Google — "novels about undermining authorial authority" — so I read more and more, realizing pretty quickly that books purporting to be about whiteness, in some way, were not at all answering this question. They seemed to be doing the opposite: centering stories of whiteness, making it into an identity that can be consumed, and that leads to fascism. So I kept looking until I came across Roberto Bolaño’s Nazi Literature in the Americas. I'd read Savage Detectives and a few of his novellas by that point, but I'd never heard anyone talk about this one (though Mark Haber is doing his part to correct that now), and that's because it's a failure of a story. There is no plot. It is encyclopedic in nature, there are barely any recurring characters, details appear randomly chosen and give no sense of the fictional historical figures described. It's difficult to keep the many made-up titles of books straight, so much so that Bolaño includes a fictional bibliography of fascist literature at the end of the book). It is dreadfully boring. And yet, I think this is one of Bolaño’s most important works, because it tells no story of whiteness, and in that tells us everything we need to know.

I think he is saying that story will not hold us. It will betray us and bend us to the will of the powerful. The most radical writers do not tell stories, or at least they don't tell good stories, because they have seen how violent and powerful story can be. Instead, they use image and language and sometimes metaphor and other oblique techniques to speak to those outside the story. So when I say I believe in literature, that's what I believe in. I don't believe in the power of story, or rather, I believe in the power of story to do ill. Some might call that propaganda, but I'd respond that it's a much thinner line than most people think between literature and propoganda. Whiteness is one of the stories of fascism. And it's not the only one. Judging from the level of blood shed and the violence both within and without this country over the last millennia, fascism is very, very good at telling stories; fascism may be integral to the history of story telling, in fact. That is one thing Nazi Literature is getting at, in my opinion.

And so, I rarely set out to 'tell a good story', though I often try to use the trappings of story to distract or get at something else. I think I’ve mostly failed at this so far. The lure of story has been too great that it often still catches me unawares, and I fall into the trap of plot for the sake of moving things along, often leaving behind what I really wanted to say or do with a story.

Recently I read Minor Detail by Palestinian writer Adania Shibli. The book is an extremely brutal, and at times, boring story. After spending fifty or so pages on the rape and murder in 1947 of a Bedouin woman by Israeli soldiers, the rest of the novel is about how there is no story ever told about this event. The narrator of the second half of the novel (the first half is in omniscient third) spends the rest of the book chasing down details of the story, which she read in a throwaway sentence in a newspaper article, only to continually find false leads and dead ends. Several times she thinks she's standing in front of the scene of the crime, only to realize she isn't, that the Israeli occupation has so scrambled the geography she once knew intimately that nothing looks familiar the further she travels from her claustrophobic neighborhood. She learns nothing in her travels, despite spending the rest of the novel driving and walking through increasingly remote ruins and desert checkpoints.

Think of how much story Shibli is resisting here. Think of how much story she had to resist in order to tell us about the horror of an untold story. It's perhaps only something a writer could appreciate, those who have experienced the many small and painful deaths of a story's infinite possibilities as it narrows in scope over the span of a draft. I think of these lost stories as frog eggs — thousands of chances at life, and as they hatch and grow into tadpoles, more and more will die to ensure a story of a few lives is told. A life cycle requires so much death.

Shibli resists a lot of death this way. She leaves so many lively stories, obscured and hidden from us. She could have written historical fiction, alternative history, spare and lyrical prose about generational trauma, a trauma she is familiar with as a Palestinian woman. But instead she wrote a book that almost isn’t. It’s one of the most powerful isn’t-books I’ve read, and it comes close to answering the question posed in The Racial Imaginary. Shibli isn’t writing the other, and she isn’t writing herself; she writes about an occupied history disappearing before our eyes.

In memory of Zoe, all she believed in, and her stories unwritten we’ll never read.

Events Etc.

I’ve already written quite a bit about what I’ve been reading, so instead, I’d like to invite you to the virtual panel “Trans in Place: Trans Writers on Place & Environment” on July 8 at 4:30pm PST // 7:30pm EST. This will be a roundtable discussion of sorts, with Kama La Mackerel, Kai Minosh Pyle, Kofi Opam, Camellia-Berry Grass, and myself. The event is co-sponsored by The Common and Foglifter Journal, and I’m grateful that both journals recognized the vision behind this event in bringing together trans writers and writers invested in place. My hope is that this will be the first of a series of similar conversations with different writers in the coming months in which we talk about our work and put pressure on the rather myopic genre of ‘place-based writing’. If you want to be notified of future events like this one, the thing to do is subscribe.

Publishing Opportunities

Burrow Press seeks fiction, nonfiction, and poetry for their Nature Issue, “with particular interest in the voices and work of Black, Indigenous, and people of color, LGBTQ+, women, people with disabilities, and other underrepresented communities.” Deadline August 31.

Quiet Lightning reading series seeks submissions in all genres for their “literary mixtape”, which will also be made into a book." Deadline July 9.

Queer | Art | Mentorship is seeking applications for a yearlong fellowship in which queer artists in film, literature, performance, and visual art are will be paired with a queer mentor in their discipline. Deadline July 22.

Hugo House in Seattle is hiring for several roles, including Adult Education Manager ($50-60k). Deadline ASAP.

My book A Natural History of Transition, is available now through Metonymy Press.

First time here? Subscribe below. You can find more of my writing at calangus.com.