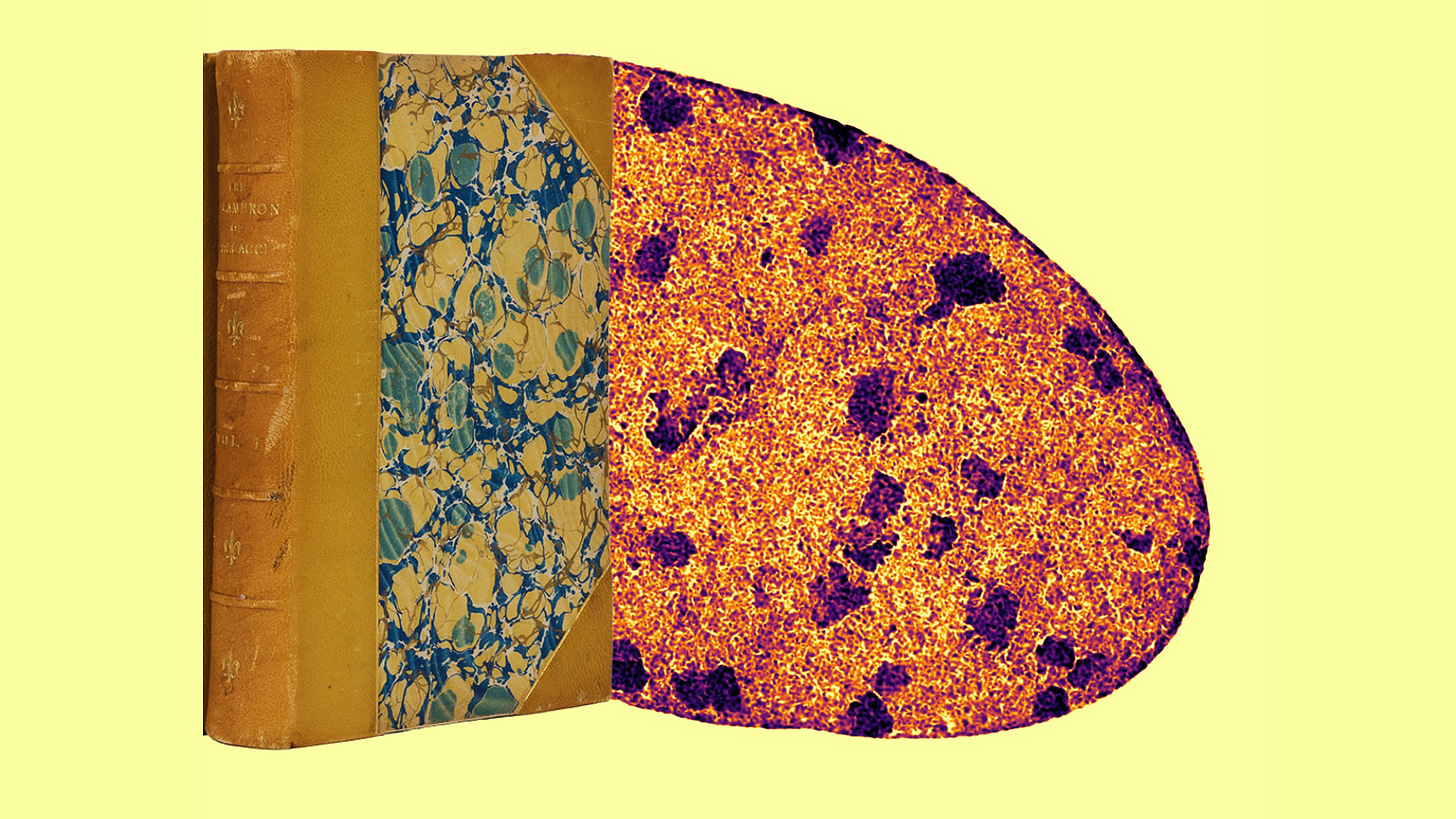

This is not an essay. If it were, I’d be embarrassed. This is an emulsification. A space where two ideas that cannot mix under normal conditions are sloshed together to form a semistable solution. I’ve been hanging on to this topic—the parallel epistemologies of how the novel and the nucleus came to be understood as independent, competitive organismal units—for the better part of a year, but the moment has never felt right for such a soft collision of ideas. If I’m being honest, it still doesn’t. But I can’t hold onto them any longer. I need to work through them, to exorcise them in this space, even if they hold no end-of-year resonance.

I write stories because they are hard to commodify. I am skeptical of any overarcing narrative on top of stories, both of my own and those of my characters. This necessarily introduces a lot of anxiety into my life. I begrudge no one who wants the whole story of themselves. To me, the idea that I have a ‘self’ is intimately related to the choice of which stories I decide to write, and how I ultimately order, collect, or opt not to hammer them into a whole. Connections between disparate parts are best left to others to determine for themselves. I relate a lot to noam keim’s ideas about the fragment shared in their recent interview in smoke and mold that “the fragment allows me to bring in things that maybe don’t quite make logical sense when you see them individually [...] I will hold my reader to an expectation that you will not passively read this, that I want you to actually engage with the text in a way where you have to struggle with me.”

In pursuit of authenticity and truth in writing, it’s the fragment that succeeds. Epic linear narrative forecloses more possibilities than it introduces in pursuit of telling a Big Long Story. I want to open up possibilities through my work. If needed, I want to stay in that space of “ill-defined tasks that have no easy procedural solution,” the sort of work most frustrating to algorithms—uncategorizeable, unreproduceable, but (at least in my opinion) still relatable. Or, on a more material plane: you know those jagged boulders placed beneath highway overpasses meant to deter people from sleeping there? I want my writing to be the opposite of whatever that gesture is. I want to invite rest and creativity, an invitation to sit and explore in the left behind, left out places.

It can be easy to assume that the popularity of the ‘linked’ story collection—i.e. that which features throughlines of characters, setting, or other closely related themes across multiple distinct short stories or novellas—is a natural progression toward complexity of the short story form. That being unable to write an ur-novel, short story writers settle for the next best thing: a dispersed narrative, much like dispersed camping allows people to set up tents wherever the state allows. But the linkage is only the latest buzzword in the literary market. Anyone who’s studied even a little bit of literary history knows that the novel did spontaneously generate—that there were stories before there were novels. In the words of Jordan Alexander Stein from his book When Novels Were Books:

“Genres do not emerge well defined and fully formed; rather, they are developed by trial and error, through practices of iteration, citation, and recognition. The meaning of any generic category—whether the tragicomic, the bildungsroman, or the noir film—depends on the human activities of identifying it, maintaining it, challenging it, and otherwise using it.”

The origins of the novel, much like the origins of life, have never been conclusively resolved; it might even be impossible to do so. In my Short Story Multiverse class, I take students through a quick and dirty (and necessarily abridged) “the novel” through the Decameron, to Don Quixote, to Balzac. We barely scratch the surface, and it leaves a lot out. Like the artificiality of A novel’s beginning, middle, and end to reality, The novel’s history is equally arbitrary, preordained, and convoluted.

The cell, like the novel, tells its own story of life; as our understanding of it changes and evolveds, so too do our ideas of what it means to be alive. The textbooks of western science show neatly sliced and diagrammed cells revealing the information-packed nucleus, full of DNA and genes passed from one generation to the next, all floating in a soup of cytoplasm and other organelles. It’s the nucleus, we’re informed, that life fights over, that competition is geared toward protecting, perpetuating, and ferrying through to the next fittest generation. This holy nuclear grail contains the entire history of not just the human genome, but of life on earth, of nature ‘red in tooth and claw.’ Of eat or be eaten.

If you believe it’s mere coincidence that the nucleus’s survival just so happens to provide capitalism with a bioessentialist origin story, it would therefore seem natural that the economic system which has dominated the global economy for the last 500 years should mirror the competition unfolding inside us on a cellular level. But there are other stories available. Stories of cells evolving not through competition but through a slow-moving evolutionary symbiosis in which squiggly, uniquely adapted single-celled organisms morphed and glommed onto one another in an attempt to live simply and best, through the cooperative path of least resistance. This merging, according to evolutionary biologists like Lynn Margulis who first popularized the theory of symbiogenesis, first occurred when one single-celled creature ate another, but the prey refused to die; instead it kept on living inside its predator. This process yielded certain advantages for both partners, and thus the mitochondria, the propellant flagellae, even the very walls of a cell were born. (‘Born’ is a misleading word to use here, but I struggle for language to talk about this story of parts-becoming-whole-rebecoming-parts.)

In this explanation of the cell, the nucleus is not the ringleader outcompeting other nuclei with its superior arrangement of organelles; rather it’s just one component of an assemblage of life, continually crashing into one another, assembling and disassembling, to the end of time. “Life did not take over the globe by combat, but by networking," she writes in Microcosmos, her book coauthored with her son Dorion Sagan. “[B]acteria invaded and came to dwell inside each other. They swarmed around sources of food, including other bacteria. Having neither immune systems nor rigid external barriers, attempting to feed they merged internally, and—with and without their viruses—they exchanged genes. Survivors of thwarted aggression formed uneasy truces. Merged, formerly independent bacteria became new kinds of complex cells.”

And what if we flip this and instead of attaching competitive cellular theory to novels, we think about the conditions under which cells are “read”? Like a text which can be interpreted in different ways, the cell, too, can be interpreted, remixed, made up and parsed through different lenses. Trans life is only the most obvious of these readings. The novel may be interpreted as a symbiotic mishmash of stories and books that have agglomerated over the centuries, with no definitive beginning, end, or type. Meanwhile, the cell can be read, like a novel, through different worldviews.

The epic loneliness of the single-celled organism, the hermetic condition of the standalone short story or the profoundly unmarketable quality of a collection of them—these are artifices the depend on us accepting the worlds they present. A linked collection is an ecosystem, not an individual exception, and like ecosystems it remains difficult to grasp and promote as a whole being. Stories made novels made of stories, and cells made nuclei which make up other cells, the competitive purity at the center of each a fiction in itself. Could it have been as simple as that? Doubtful. As usual, it feels like I’ve danced around the ideas just out of reach of my own mind. And maybe this is all just an excuse for my being uncompetitive and strange. But I have no regrets, not yet.

Upcoming

If you made it through that emulsification to the end, thank you! Here is what my late winter/spring 2025 class line-up looks like, should you be interested. All classes are sliding scale:

exoliterature: insects in fiction | thursdays, 1/23- 2/20 | on zoom, 5-7PM PST

Speculative Shorts: A Short Fiction Workshop | march - june (see description for specific dates) | on zoom, 5-7PM PST

Climate Journaling in the End Times w/ Corporeal Writing | First Tuesdays, April - July | on zoom, 5-7PM PST

I’ll also be facilitating an 8-week Digital Residency through The Seventh Wave starting March 19! More info here.

Here’s to having no regrets in 2025, living loudly, and in solidarity with the people of Palestine in their continued struggle for life against the zionist scourge of Israel. Have you explored the donations-based offerings of Workshops4Gaza? Wish to join me in donating an ongoing monthly amount to the Palestine Institute for Biodiversity & Sustainability, about which I’ve written previously? You can do so here.

You always stretch my thinking in fascinating ways!