In her book Love Child’s Hotbed of Occasional Poetry, Nikky Finney writes that her journals are “the garden of my interior”, which I think is a beautiful way of thinking about the private writing and scrawling and diagramming we do as writers when no one is looking. And if journals are where we dig around in the dirt on our own, I’ve been thinking a lot about how this newsletter can become more like a community garden. I want it to be a space where people can come and take what they need, maybe leave something for another reader in the form of resources, validation, or otherwise.

Having enjoyed various community garden plots in the past, it’s also a place where I make mistakes, get told I’m wrong, and learn from those tending around me tending to their own patches. I have the same hopes for this space (see below for a special subscriber giveaway to kick this off.)

When the book in this picture was printed in 1971, its author was still living in Cuba, and would be for another nine years until he fled to the U.S. on the Mariel boatlift. In 1974 he was imprisoned for his writing, his criticism of Castro’s regime, and his refusal to renounce his homosexuality, and throughout the seventies when foreign writers visited Cuba and asked to see Reinaldo Arenas, the response was ‘Reinaldo who?’ from government officials and other writers who were afraid of being persecuted by association.

Reinaldo’s books were not instruction manuals, nor were they idealistic or moralizing or even concerned with engaging the reader all of the time. They’re not like anything else I’ve read. Much of the time their narrative is nonlinear, if not outright difficult to follow, confusing in its refusal of chronology—the kind of book that is difficult to get published today. Although he spent much of his time in El Morro prison writing letters to families and loved ones for his fellow inmates, his novels sacrifice sense for the absurd, the grotesque, and the downright raunchy (think a monk swimming in oceans of semen). Many of his novels begin with a character’s childhood in which horrific, extravagant abuse is enacted on the child by guardians who have themselves have been subjected to violence and terror over throughout their lives. Still, causation is not a main driver in his plots, if they can be called such; instead what you’re left with is the book equivalent of a very long scream, interspersed with sex and crazy maybe-dream sequences. Much like life.

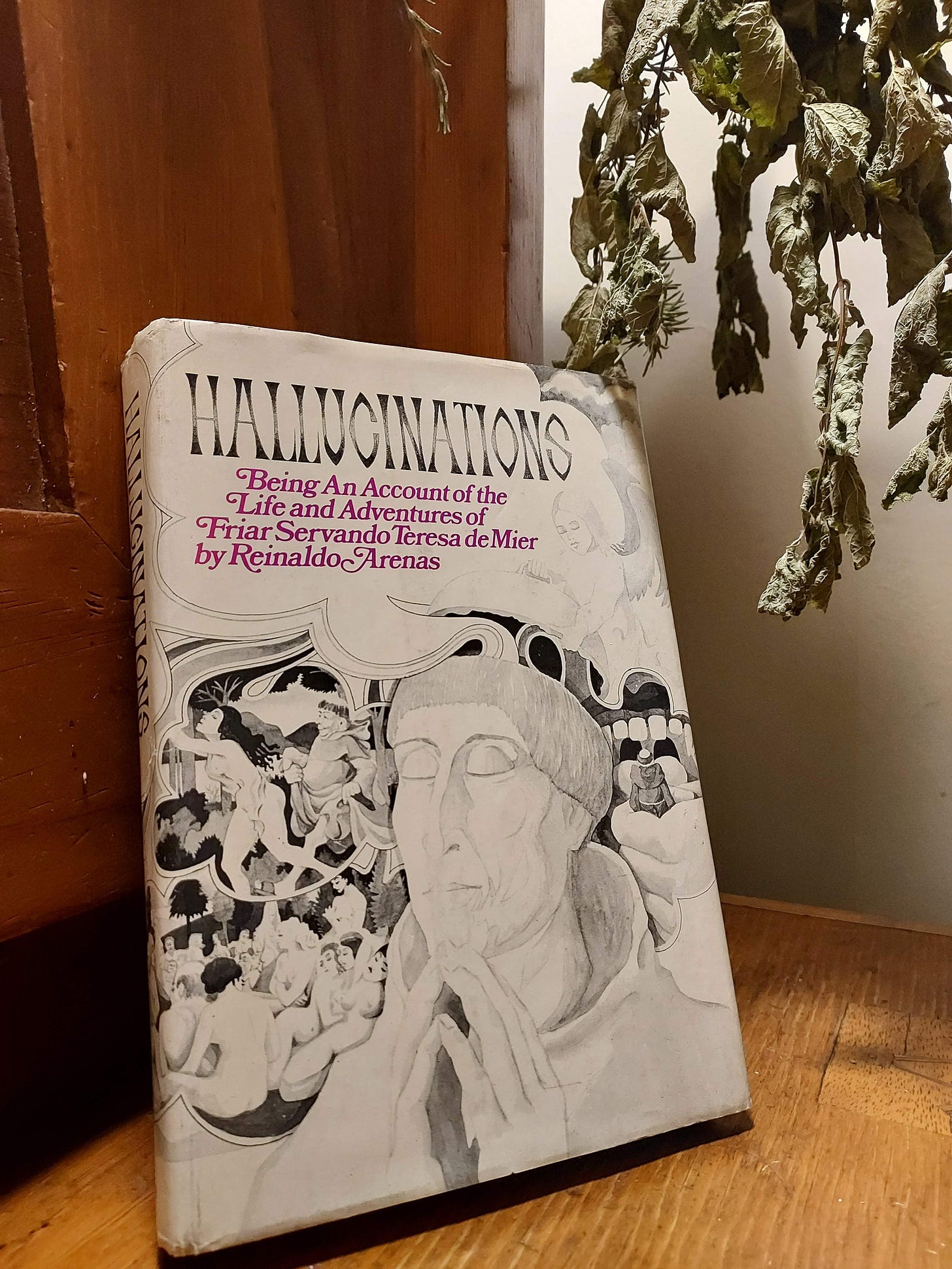

After his death of AIDS in 1990 in New York, there was a flurry of interest in his work and life, culminating in a biopic in 2000 Before Night Falls, which critics praised. Since then, his books have fallen out of fashion*, which was lucky for me because it meant it was easy to find a cheap first edition of Hallucinations. From the explicitly sexual illustrations on the jacket featuring priests and nuns, to the font and the deep violet boards, I absolutely fetishize this book, as it was meant to be fetishized. It’s a totem of a different time, when raunchy novels by soon-to-be political prisoners were lavishly published as objects that would continue to exist even after the death of the author, for future readers to find and obsess over. Maybe that sounds like I buy too much into the commodification of books.It’s true that there are many beautifully printed translations in paperback these days, but it’s hard to imagine most of these books surviving the long haul. What is a relatively wise business decision in the present (forgoing the traditional hardcover in order to more affordably present unknown authors to the public) ends up denying future generations the gratification of discovering someone who’s been forgotten. There’s a way in which an old hardcover feels permanently underripe in my hands, like it still has secrets no one else has been able to pry free.

I didn’t used to feel this way about first editions. When I first worked in a bookstore I would wrap 200+ copies of a new hardcover novel in mylar every month, which I then shipped to our First Editions Club members as our best estimate of what books would appreciate the most over time based on some ineffable combination of literary merit, awards, taste, and fairy dust. It was astounding to me that this was a way people engaged with books: receive a box in the mail once a month, shelve that book and wait for it to earn you money when you die. I don’t know how many of those customers even read the books they received.

These days, it’s extremely rare that I purchase a new hardcover for myself. Books are heavy and take up space, and I’m not willing to fill up my extremely limited shelf space with books I’m not sure I’ll even like. Instead I reserve the coveted middle shelves for older books, usually hardback but not always, for how they remind me of the real people who were alive to see their words in print in this edition for the first time, even if it had to be in a foreign language due to the circumstances of censorship in their home country; it reminds me that place and time are as much participants in this project we call literature and legacy and reading as the words on the page or the blurbs on the back.

*In researching this piece, I realized that PRH reprinted Before Night Falls last year as part of a series of five “American classics” that encourage new readers to discover “literary gifts of personal inspiration, intellectual engagement, and creative originality.” The cover is bland and suggestive of nothing other than contemporary publishing’s fetish for type that looks good on a screen. Don’t be fooled — this new edition is actually more expensive than most first editions available, which have a smoldering, sexy Reinaldo on the front cover looking directly at you, deemed too arousing for modern audiences, apparently.

What I’m Giving You to Read

As mentioned above the fold, I want there to be more give and take here between readers and myself, and so I’m excited to start partnering with more people and organizations to bring more bookish stuff to you. This week I’m partnering with The Center for the Art of Translation to give away a 2022 Two Lines Press subscription—8 books in total—to one randomly chosen subscriber to Sex Weather Climate Death. If you’ve been here awhile, you’ll know I love Two Lines for their wide-ranging approach to translation couched in beautiful editions (sometimes even hardcover, against all odds!). I want queer and trans writers to read more translation (even do more translation). I’ll announce the winner on Feb 15.

Publishing Opportunities

Brick Books is open to submissions of full-length poetry manuscripts until May 31. Canadian writers only.

The Institute of American Indian Arts’ Low Residency MFA program is hiring a Program Coordinator. (Sorry, no deadline or salary listed.)

Changes Press is accepting submissions of poetry and translations for Changes Review on a rolling deadline.

Annulet Poetics is open for submissions of poetry, reviews, criticism and more for its third issue. Deadline March 15.

Guernica’s Global Spotlights is accepting submissions of fiction and nonfiction in translation. Pays $100.