This will not be a linear progression. On a microscopic scale, things like negative pressure and salts and ions control the narrative flow. I will pretend the same goes here.

Last week I was walking in my local park. Caution tape quivered around a new sapling. A hummingbird fed at the trunk of a douglas fir freshly sapped, no bullseye of petals to guide it just the solid safety of a tree that runs sweet as a backup. My intent had been to go for a run, then that turned into a walk, which turned into a long, slow sit to watch the hummingbird and the caution tape. I wouldn’t have seen these things if I’d been moving my body fast. But I do too much sitting and I need to move to stay healthy. A conundrum.

We found a katydid on the lampshade in our living room. I’d never found one inside before. In researching what it meant, I learned about the Chinese tradition of bird and flower painting, or more accurately bird, flower, fish and insect paintings, or 花鸟画 (huaniaohua). Largely formalized through traditional painting, this is the appreciation of nature’s smallest, most inconspicuous elements. There is so much more to learn. The katydid means abundance, by the way. I probably could have told you that based on its origami folded green wings alone.

I am very sad about the moon. Lots of articles lately about efforts from countries around the globe seek to put a permanent human presence on the moon in my lifetime. I’m already grieving its mystery without any people. It feels very much like we should take a vote on this. It wouldn’t solve anything, as the richest will still do whatever they want, but at least then I’d know where everyone stands.

Can the moon be considered an unpeopled preserve of the imagination? I don’t know. I don’t know if it should be, either. I know it’s in lots of stories and full of trash and our feces already, so maybe I mourn an imaginary place. In fact, I know I mourn an imaginary place. I have never nor will I ever go there. That’s sort of the point.

In light of this, I’m feeling conflicted about science fiction. I want to write stories that take place on other planets, on moons, in the vast outerness of space, but I wonder at the relationship between science fiction stories and the push for space colonization. Has this always been the end game of science fiction? Providing a blueprint for how humanity can use up this planet and leave it behind? Who can imagine space, who can imagine the deep sea, the quantum realm, the space inside a cell, and not claim it? I don’t think imagination should be a tool of colonization, but that’s what ends up happening. Impact trumps intention, and all that.

Take the christian right and the “pro-life” faction and their hyperbolic posters claiming life starts at inception. They would have us believe that they care about the smallest life—the embryo—because they can imagine its nonexistent heart beating. In their small minds, they colonize the womb with their certainty that that’s the smallest life can get, and that it must be protected. So boastful, so shortsighted. There is much more life, more complexly and in smaller concentrations in a patch of moss more worth saving than a few human epithelial cells.

Yuri Herrera’s Ten Planets has been one thing that’s reassured me recently that not all space literature need insist on expansion, that some can resist and withhold the blueprints. Garrick Imatani’s continued and slow thinking with Tomanowas, also known as the Willamette Meteorite, over a series of years and its many transits across space and time before its current imprisonment inside a museum is another. I’ve been privileged to follow him thinking about this (not ‘follow’ in the social media sense, but to simply follow his train of thought through his work over an extended period of time). Lately I’ve enjoyed watching his video The Drift with my students in *sigh*ence class, silently watching together the repatriation of Tomanowas through an unpeopled topia (u- or dys- is inconclusive). It feels reverential every time.

When an artist thinks and writes about one thing over a long period of time, that also means others get to think slowly with them, through them, using them and their work as a sort of focusing or lengthening prism. This kind of thinking refutes the idea that artists must produce commodities, that thinking in and of itself is luxurious without a transaction attached.

I like to think that this is what this newsletter has become. Me thinking slowly with a range of climate- and book-adjacent topics over a long period of time, so that you can think with me. It’s not perfect—I’m still spawning commodities. One as yet unpublished book, STREAM, will hopefully be coming soon, and in the meantime STREAM itself has spawned a chapbook (more soon). But the great thing about books as slow commodities is we get to decide when they’re done, even long after they’ve been published, by reading and reinterpreting them.

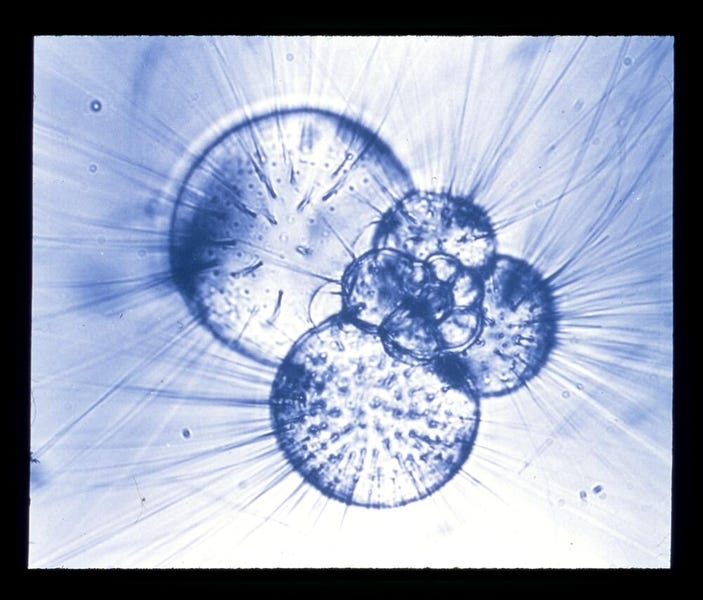

Planets, moons, meteorites, books—these are all relatively big things, and this is supposed to be about the very small. I’m failing to articulate myself here. I keep writing half a newsletter and then waiting for the rest of it to congeal, to show itself, waiting until it feels finished. But they never feel finished. Like the zoon or the zooid—individual organisms that make up one colonial animal—each one exists independently but can’t really be understood on its own. They need to link up and form one long eerie siphonophore chain to make any kind of statement, even an unintelligible one transparent and drifting a mile long through the water column, trailing impenetrable meaning behind it like a jelly streamer.

For a brief period in the early twentieth century, it was considered an experimental health breakthrough to inject the sick with seawater. I read this in a paper titled “Sea-water Treatment, Given by Subcutaneous Injection with the Results Obtained in Children,” itself a transcription of research delivered at the American Medical Association’s 60th Annual Session held in 1909. Injections of this “marine scrum” was thought to have regenerative effects on cells impacted by disease. I guess the thinking was that both the cell and the sea contain salty water.

A few weeks ago I was on the other coast walking a headland on the Eastern Shore of Nova Scotia, unceded land of the Mi'kmaq peoples. It’s a hike I’ve done many times, up a mown rise and along a lagoon that softens the tides where sea otters go to brood their young. I used to hike it with family, but most are either too old or gone now to do it with me. It’s alright. I like doing it alone, waking before dawn so I can be the only person on the trail. The day before I’d seen a large black bear cross the road in front of my car, and so I brought a bell with me to ring on the trail and warn any of its friends that I was coming around the corner. I doubt there were any bears out there. I think I was mostly alerting the ghosts that here comes an open soul.

At the very edge of the headland where the rock cliff drops away to the sea it’s a carpet of coarse moss, maybe heather, I just realized I don’t actually know what it’s called. We’ve just always called it “quoddy grass.” It makes for a soft spot to sit and watch the waves. I was doing so, eating a sandwich and meditating with my eyes closed, and when I opened them I was staring right through a wave at the blotchy coat of a harbor seal. It took me a minute to figure out what I was seeing. The seal moved languidly, unrushed, using the scroll of the wave to push its body along effortlessly through the water. It was maybe 20 yards away (this measuring of distance away from another animal, what’s that about?). Usually when I see seals they know I’m there. They poke their heads above the water and exhale through their nostrils noisily so I can hear their particular brand of annoyance and curiosity at the imposition of my presence. This seal didn’t know I was there, up a few feet, watching its round body ride the tide. And all I’d had to do was close my eyes and open them again.

Upcoming: In-Person Workshops & New Stories in Print

I’m hosting another FLOQ open reading and workshop on Thursday, September 21st back at Bishop & Wilde. The workshop starts at 5pm (space is limited, so please RSVP here), then after a break the open reading will get started at 7pm in the bookstore, with featured reader Jzl Jmz. Both events are free, and all are welcome at the reading (the workshop is reserved for trans and nonbinary folks). I hope you’ll join us at this evening in celebration of Portland’s trans lit community. It’ll be the last one I’m hosting for 2023! Will it return next year? I hope so!

I’m offering two in-person workshops on Saturdays in September. “Secret Garden: Growth” on September 16th, and “Secret Garden: Decay” on September 30th. Fall is here, so let’s break some shit down in a beautiful place. Sliding scale, NOTAFLOF. More info at the link.

I’ve been really focused on teaching lately, but I am still writing. I’ll have two new stories out this fall, one in Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet and another in Michigan Quarterly Review. Both will be in print, and so I’m thinking about doing an Instagram live or some other live virtual reading of one or both of them. I’ve got no idea if that’s something anyone would be interested in (maybe if it’s late at night you can fall asleep to it?) but print work needs more love.

Finally, a good number of you are heading back to school or maybe starting an MFA for the first time. To you I say: good luck!

Be well everyone. And keep in touch,

Cal